Arctic Refuge drilling controversy

The question of whether to drill for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) has been an ongoing political controversy in the United States since 1977.[1] As of 2017, Republicans have attempted to allow drilling in ANWR almost fifty times, finally being successful with the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.[2]

ANWR comprises 19 million acres (7.7 million ha) of the north Alaskan coast.[3] The land is situated between the Beaufort Sea to the north, Brooks Range to the south, and Prudhoe Bay to the west. It is the largest protected wilderness in the United States and was created by Congress under the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980.[4] Section 1002 of that act deferred a decision on the management of oil and gas exploration and development of 1.5 million acres (610,000 ha) in the coastal plain, known as the "1002 area".[5] The controversy surrounds drilling for oil in this subsection of ANWR.

Much of the debate over whether to drill in the 1002 area of ANWR rests on the amount of economically recoverable oil, as it relates to world oil markets, weighed against the potential harm oil exploration might have upon the natural wildlife, in particular the calving ground of the Porcupine caribou.[6][7] In their documentary Being Caribou the Porcupine herd was followed in its yearly migration by author and wildlife biologist Karsten Heuer and filmmaker Leanne Allison to provide a broader understanding of what is at stake if the oil drilling should happen and educating the public. There has been controversy over the scientific reports' methodology and transparency of information during the Trump administration. Although there have been complaints from employees within the Department of the Interior,[citation needed] the reports remain the central evidence for those who argue that the drilling operation will not have a detrimental impact on local wildlife.

On December 3, 2020, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) gave notice of sale for the Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program in the ANWR with a livestream video drilling rights lease sale scheduled for January 6, 2021. The Trump administration issued the first leases on January 19, 2021. On President Joe Biden's first day in Office, he issued an executive order for a temporary moratorium on drilling activity in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.[8][9] On June 1, 2021, Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland suspended all Trump-era oil and gas leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge pending a review of how fossil fuel drilling would impact the remote landscape.[10] On September 6, 2023, the Biden administration cancelled the leases.[11]

History

[edit]

Before Alaska was granted statehood on January 3, 1959, virtually all 375 million acres (152 million ha) of the Territory of Alaska was federal land and wilderness. The act granting statehood gave Alaska the right to select 103 million acres (42 million ha) for use as an economic and tax base.[12]

In 1966, Alaska Natives protested a federal oil and gas lease sale of lands on the North Slope claimed by Natives. Late that year, Secretary of the interior Stewart Udall ordered the lease sale suspended. Shortly thereafter announced a 'freeze' on the disposition of all federal land in Alaska, pending congressional settlement of Native land claims.[12][13]

These claims were settled in 1971 by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, which granted them 44 million acres (18 million ha). The act also froze development on federal lands, pending a final selection of parks, monuments, and refuges. The law was set to expire in 1978.[14]

Toward the end of 1976, with the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System virtually complete, major conservation groups shifted their attention to how best to protect the hundreds of millions of acres of Alaskan wilderness unaffected by the pipeline.[15] On May 16, 1979, the United States House of Representatives approved a conservationist-backed bill that would have protected more than 125 million acres (51 million ha) of federal lands in Alaska, including the calving ground of the nation's largest caribou herd. Backed by President Jimmy Carter, and sponsored by Morris K. Udall and John B. Anderson, the bill would have prohibited all commercial activity in 67 million acres (270,000 km2) designated as wilderness areas. The U.S. Senate had opposed similar legislation in the past and filibusters were threatened.[16]

On December 2, 1980, Carter signed into law the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, which created more than 104 million acres (42 million ha) of national parks, wildlife refuges, and wilderness areas from federal holdings in that state. The bill allowed drilling in ANWR, but not without Congress's approval and the completion of an Environmental Impact Study (EIS).[17] Both sides of the controversy announced they would attempt to change it in the next session of Congress.[18]

Section 1002 of the act stated that a comprehensive inventory of fish and wildlife resources would be conducted on 1.5 million acres (0.61 million ha) of the Arctic Refuge coastal plain (1002 Area). Potential petroleum reserves in the 1002 Area were to be evaluated from surface geological studies and seismic exploration surveys. No exploratory drilling was allowed. These studies and recommendations for future management of the Arctic Refuge coastal plain were to be prepared in a report to Congress.

In 1985, Chevron drilled a 15,000 foot (4,600 m) test bore, known as KIC-1, on a private tract inside the border of ANWR. The well was capped, and the drilling platform, dismantled. The results are a closely held secret.[19][20]

In November 1986, a draft report by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service recommended that all of the coastal plain within the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge be opened for oil and gas development. It also proposed to trade the mineral rights of 166,000 acres (67,000 ha) in the refuge for surface rights to 896,000 acres (363,000 ha) owned by corporations of six Alaska native groups, including Aleuts, Eskimos and Tlingits. The report said that the oil and gas potentials of the coastal plain were needed for the country's economy and national security.[21]

Conservationists said that oil development would unnecessarily threaten the existence of the Porcupine caribou by cutting off the herd from calving areas.[22] They also expressed concerns that oil operations would erode the fragile ecological systems that support wildlife on the tundra of the Arctic plain. The proposal faced stiff opposition in the House of Representatives. Morris Udall, chairman of the House Interior Committee, said he would reintroduce legislation to turn the entire coastal plain into a wilderness area, effectively giving the refuge permanent protection from development.[21]

On July 17, 1987, the United States and the Canadian government signed the "Agreement on the Conservation of the Porcupine Caribou Herd," a treaty designed to protect the species from damage to its habitat and migration routes.[23] Canada has a special interest in the region because its Ivvavik National Park and Vuntut National Park borders the refuge. The treaty required an impact assessment and required that where activity in one country is "likely to cause significant long-term adverse impact on the Porcupine Caribou Herd or its habitat, the other Party will be notified and given an opportunity to consult prior to final decision".[23] This focus on the Porcupine caribou led to the animal becoming a visual rhetoric or symbol of the drilling issue much in the same way the polar bear has become the image of global warming.[24]

In March 1989, a bill permitting drilling in the reserve was "sailing through the Senate and had been expected to come up for a vote"[25] when the Exxon Valdez oil spill delayed and ultimately derailed the process.[26]

In 1996, the Republican-majority House and Senate voted to allow drilling in ANWR, but this legislation was vetoed by President Bill Clinton. Toward the end of his presidential term, environmentalists pressed Clinton to declare the Arctic Refuge a U.S. National Monument. Doing so would have permanently closed the area to oil exploration. While Clinton did create several refuge monuments, the Arctic Refuge was not among them.

A 1998 report by the U.S. Geological Survey estimated that there was between 5.7 billion barrels (910,000,000 m3) and 16.0 billion barrels (2.54×109 m3) of technically recoverable oil in the designated 1002 area, and that most of the oil would be found west of the Marsh Creek anticline.[27][28] The term technically recoverable oil is based on the price per barrel where oil that is more costly to drill becomes viable with rising prices.[29] When non-federal and Native areas are excluded, the estimated amounts of technically recoverable oil are reduced to 4.3 billion barrels (680,000,000 m3) and 11.8 billion barrels (1.88×109 m3). These figures differed from an earlier 1987 USGS report that estimated smaller quantities of oil and that it would be found in the southern and eastern parts of the 1002 area. However, the 1998 report warned that the "estimates cannot be compared directly because different methods were used in preparing those parts of the 1987 Report to Congress".[28]

In the 2000s, the House of Representatives and Senate repeatedly voted on the status of the refuge. President George W. Bush pushed to perform exploratory drilling for crude oil and natural gas in and around the refuge. The House of Representatives voted in August 2001 to allow drilling.[30][31][32] In April 2002, the Senate rejected it.[33][34] In 2001, Time's Douglas C. Waller said the Arctic Refuge drilling issue has been used by both Democrats and Republicans as a political device, especially through contentious election cycles.[35]

The Republican-controlled House of Representatives again approved Arctic Refuge drilling as part of the 2005 energy bill on April 21, 2005, but the House-Senate conference committee later removed the Arctic Refuge provision. The Republican-controlled Senate passed Arctic Refuge drilling on March 16, 2005, as part of the federal budget resolution for the fiscal year 2006.[36][37] That Arctic Refuge provision was removed during the reconciliation process due to Democrats in the House of Representatives who signed a letter stating they would oppose any version of the budget that had Arctic Refuge drilling in it.[38]

On December 15, 2005, Republican Alaska Senator Ted Stevens attached an Arctic Refuge drilling amendment to the annual defense appropriations bill. A group of Democratic senators led a successful filibuster of the bill on December 21, and the language was subsequently removed.[39]

On June 18, 2008, President George W. Bush pressed Congress to reverse the ban on offshore drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in addition to approving the extraction of oil from shale on federal lands. Despite his previous stance on the issue, George W. Bush said the growing energy crisis was a major factor for reversing the presidential executive order issued by his father President George H. W. Bush in 1990, which banned coastal oil exploration, and oil and gas leasing on most of the outer continental shelf. In conjunction with the presidential order, the Congress had enacted a moratorium on drilling in 1982 and renewed it annually.[40]

In 2014, President Barack Obama proposed declaring an additional 5 million acres of the refuge as a wilderness area, which would put a total of 12.8 million acres (5.2 million ha) of the refuge permanently off-limits to drilling or other development, including the coastal plain where oil exploration has been sought.[41]

In 2017, the Republican-controlled House and Senate included in tax legislation a provision that would open the 1002 area of ANWR to oil and gas drilling. It passed both the Senate and House of Representatives on December 20, 2017.[42] President Trump signed it into law on December 22, 2017.[43][44][45]

In September 2019, the Trump administration said they would like to see the entire coastal plain opened for gas and oil exploration, the most aggressive of the suggested development options. The Interior Department's Bureau of Land Management BLM filed a final environmental impact statement and planned to start granting leases by the end of 2019. In a review of the statement, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said the BLM's final statement underestimated the climate impacts of the oil leases because they viewed global warming as cyclical rather than human-made. The administration's plan calls for "the construction of as many as four places for airstrips and well pads, 175 miles of roads, vertical supports for pipelines, a seawater-treatment plant and a barge landing and storage site."[46][47]

On August 17, 2020, the Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt announced that the required reviews were complete and oil and gas drilling leases in the ANWR's coastal plain could now be put up for auction.[48][49] Both the Republican governor Mike Dunleavy and the Republican senators Lisa Murkowski and Dan Sullivan approved the sales of the leases.[48] There have been no recent seismic studies of how much oil there is in the area. Previous studies undertaken in the 1980s used older technologies that were "relatively primitive", according to the New York Times.[48] It is also unknown how many oil and gas companies would bid on the leases, which would involve years of litigation. Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, and other banks stated they would not finance drilling in the ANWR, after a public outcry in support of the native Gwichʼin people and against the potential impact it would have on climate change.[48] In September 2020, the attorneys general of 15 states, led by Bob Ferguson, filed a federal lawsuit to stop any drilling, alleging that the Administrative Procedure Act and the National Environmental Policy Act had been violated.[50]

On December 3, 2020, the Bureau of Land Management gave notice of sale for the Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program in the ANWR, with the Federal Register Notice published on December 7.[51] The livestream video drilling rights lease sale was scheduled for January 6, 2021.[52] Of the twenty-two tracts up for auction, full bids were offered for only eleven tracts. An Alaskan state entity, the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority, won the bids on nine tracts. Two small independent companies, Knik Arm Services LLC and Regenerate Alaska Inc, won one tract each. The auction generated $14.4 million, lower than the $1.8 billion estimate from the Congressional Budget Office in 2019, and the auction did not receive bids from any oil and gas companies.[53]

On June 1, 2021, Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland suspended all Trump-era oil and gas leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge pending a review of how fossil fuel drilling would impact the remote landscape.[10] Indigenous and conservation groups urged Biden to make the suspension permanent. On September 6 2023, the Biden administration cancelled the leases.[11]

Department of Energy projections and estimates

[edit]Estimates of oil reserves

[edit]

In 1998, the USGS estimated that between 5.7 and 16.0 billion barrels (2.54×109 m3) of technically recoverable crude oil and natural gas liquids are in the coastal plain area of ANWR, with a mean estimate of 10.4 billion barrels (1.65×109 m3), of which 7.7 billion barrels (1.22×109 m3) lie within the Federal portion of the ANWR 1002 Area.[27][28] In comparison, the estimated volume of undiscovered, technically recoverable oil in the rest of the United States is about 120 billion barrels (1.9×1010 m3).[55]

The ANWR and undiscovered estimates are categorized as prospective resources and therefore, not proven oil reserves. The United States Department of Energy (DOE) reports U.S. proved reserves are roughly 29 billion barrels (4.6×109 m3) of crude and natural gas liquids, of which 21 billion barrels (3.3×109 m3) are crude.[56] A variety of sources compiled by the DOE estimate world proved oil and gas condensate reserves to range from 1.1 to 1.3 trillion barrels (170×109 to 210×109 m3).[57]

The DOE reported there is uncertainty about the underlying resource base in ANWR. "The USGS oil resource estimates are based largely on the oil productivity of geologic formations that exist in the neighboring State lands and which continue into ANWR. Consequently, there is considerable uncertainty regarding both the size and quality of the oil resources that exist in ANWR. Thus, the potential ultimate oil recovery and potential yearly production are highly uncertain."[55]

In 2010, the USGS revised an estimate of the oil in the National Petroleum Reserve–Alaska (NPRA), concluding that it contained approximately "896 million barrels of conventional, undiscovered oil".[58] The NPRA is west of ANWR. The reason for the decrease is because of new exploratory drilling, which showed that many areas that were believed to hold oil actually hold natural gas.

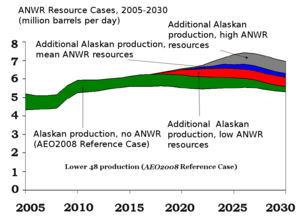

The opening of the ANWR 1002 Area to oil and natural gas development is projected to increase U.S. crude oil production starting in 2018. In the mean ANWR oil resource case, additional oil production resulting from the opening of ANWR reaches 780,000 barrels per day (124,000 m3/d) in 2027 and then declines to 710,000 barrels per day (113,000 m3/d) in 2030. In the low and high ANWR oil resource cases, additional oil production resulting from the opening of ANWR peaks in 2028 at 510,000 and 1.45 million barrels per day (231,000 m3/d), respectively.[55]

Between 2018 and 2030, cumulative additional oil production is projected to be 2.6 billion barrels (410,000,000 m3) for the mean oil resource case, while the low and high resource cases project a cumulative additional oil production of 1.9 and 4.3 billion barrels (680,000,000 m3), respectively.[55] In 2017, the United States consumed 19.877 million barrels per day (3,160,200 m3/d) of petroleum products. It produced roughly 9.355 million barrels per day (1,487,300 m3/d) of crude oil, and imported 7.912 million barrels per day (1,257,900 m3/d) of crude and 2.163 million barrels per day (343,900 m3/d) of petroleum products.[59]

Projected impact on global oil price

[edit]The total production from ANWR would be between 0.4 and 1.2 percent of total world oil consumption in 2030. Consequently, ANWR oil production is not projected to have any significant impact on world oil prices.[55] Furthermore, the Energy Information Administration does not feel ANWR will affect the global price of oil when past behaviors of the oil market are considered. "The opening of ANWR is projected to have its largest oil price reduction impacts as follows: a reduction in low-sulfur, light crude oil prices of $0.41 per barrel (2006 dollars) in 2026 for the low oil resource case, $0.75 per barrel in 2025 for the mean oil resource case, and $1.44 per barrel in 2027 for the high oil resource case, relative to the reference case."[55] "Assuming that world oil markets continue to work as they do today, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) could neutralize any potential price impact of ANWR oil production by reducing its oil exports by an equal amount."[55]

Support for drilling

[edit]President Donald Trump said that he had little interest in drilling in the Arctic Refuge until a friend "who's in that world and in that business" called and told him Republicans have been trying to do so for decades — so he had it included in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. "After that I said, 'Oh, make sure that's in the [tax] bill,'" he said in a speech at the GOP congressional retreat.[60]

President George W. Bush's administration supported drilling in the Arctic Refuge, saying that it could "keep [America]'s economy growing by creating jobs and ensuring that businesses can expand [and] it will make America less dependent on foreign sources of energy", and that "scientists have developed innovative techniques to reach ANWR's oil with virtually no impact on the land or local wildlife."[61][62]

Both of Alaska's U.S. senators, Republicans Lisa Murkowski and Dan Sullivan, have indicated they support ANWR drilling.

Voice of the Arctic Iñupiat, a nonprofit organization that advocates for Iñupiaq people and culture, supports ANWR development.[63]

A June 29, 2008, Pew Research Poll reported that 50% of Americans favor drilling of oil and gas in ANWR while 43% oppose (compared to 42% in favor and 50% opposed in February of the same year).[64] A CNN opinion poll conducted on August 31, 2008, reported 59% favor drilling for oil in ANWR, while 39% oppose it.[64] In the state of Alaska, residents receive annual dividends from a permanent fund funded partially by oil-lease revenues. In 2013, the dividend came to $900 per resident.[65]

The United States Department of Energy estimates that ANWR oil production between 2018 and 2030 would reduce the cumulative net expenditures on imported crude oil and liquid fuels by an estimated $135 to $327 billion (2006 dollars), reducing the foreign trade deficit.[citation needed]

Arctic Power cites a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service report stating that 77 of the 567 wildlife refuges in 22 states had oil and gas activities. Louisiana had the most with 19 units, followed by Texas, which had 11 units. Furthermore, oil or gas was produced in 45 of the 567 units located in 15 states. The number of producing wells in each unit ranged from one to more than 300 in the Upper Ouachita National Wildlife Refuge in Louisiana.[66]

Opposition to drilling

[edit]

President Joe Biden signed an executive order to halt new Arctic drilling on his first day in office. Biden subsequently suspended oil drilling leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in June 2021. "President Biden believes America's national treasures are cultural and economic cornerstones of our country," White House National Climate Advisor Gina McCarthy said in a statement.[67] On September 6 2023, the Biden administration cancelled the leases.[11]

Former president Barack Obama also opposed drilling in the Arctic Refuge.[68] In a League of Conservation Voters questionnaire, Obama said, "I strongly reject drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge because it would irreversibly damage a protected national wildlife refuge without creating sufficient oil supplies to meaningfully affect the global market price or have a discernible impact on U.S. energy security." Senator John McCain, while running for the 2008 Republican presidential nomination, said, "As far as ANWR is concerned, I don't want to drill in the Grand Canyon, and I don't want to drill in the Everglades. This is one of the most pristine and beautiful parts of the world."[69]

In 2008, the U.S. Department of Energy reported uncertainties about the USGS oil estimates for ANWR and the projected effects on oil price and supplies. "There is little direct knowledge regarding the petroleum geology of the ANWR region. ... ANWR oil production is not projected to have a large impact on world oil prices. ... Additional oil production resulting from the opening of ANWR would be only a small portion of total world oil production, and would likely be offset in part by somewhat lower production outside the United States."[55]

The DOE reported that annual United States consumption of crude oil and petroleum products was 7.55 billion barrels (1.200×109 m3) in 2006.[70] In comparison, the USGS estimated that the ANWR reserve contains 10.4 billion barrels (1.65×109 m3), although only 7.7 billion barrels (1.22×109 m3) were thought to be within the proposed drilling region.[27][28]

"Environmentalists and most congressional Democrats have resisted drilling in the area because the required network of oil platforms, pipelines, roads and support facilities, not to mention the threat of foul spills, would play havoc on wildlife. The coastal plain, for example, is a calving home for some 129,000 caribou."[35]

The NRDC has said that drilling would not take place in a compact, 2,000-acre (810 ha) space as proponents say, but would create "a spiderweb of industrial sprawl across the whole of the refuge's 1.5-million-acre (0.61-million ha) coastal plain, including drill sites, airports and roads, and gravel mines, spreading across more than 640,000 acres (260,000 ha). The NRDC also said there is danger of oil spills in the region.[71][72]

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has said that the 1002 area has a "greater degree of ecological diversity than any other similar sized area of Alaska's north slope". The FWS also states, "Those who campaigned to establish the Arctic Refuge recognized its wild qualities and the significance of these spatial relationships. Here lies an unusually diverse assemblage of large animals and smaller, less-appreciated life forms, tied to their physical environments and to each other by natural, undisturbed ecological and evolutionary processes."[73]

Prior to 2008, 39% of the residents of the United States[64] and a majority of Canadians opposed drilling in the refuge.[74]

The Alaska Inter-Tribal Council (AI-TC), which represents 229 Native Alaskan tribes, officially opposes any development in ANWR.[75] In March 2005, Luci Beach, the executive director of the steering committee for the Native Alaskan and Canadian Gwich'in tribe (a member of the AI-TC), during a trip to Washington D.C., while speaking for a unified group of 55 Alaskan and Canadian indigenous peoples, said that drilling in ANWR is "a human rights issue and it's a basic Aboriginal human rights issue".[76][77] The Gwich'in tribe adamantly believes that drilling in ANWR would have serious negative effects on the calving grounds of the Porcupine caribou herd that they partially rely on for food.[78]

A part of the Inupiat population of Kaktovik, and 5,000 to 7,000 Gwich'in peoples feel their lifestyle would be disrupted or destroyed by drilling.[79] The Inupiat from Point Hope, Alaska recently passed resolutions[80] recognizing that drilling in ANWR would allow resource exploitation in other wilderness areas. The Inupiat, Gwitch'in, and other tribes are calling for sustainable energy practices and policies. The Tanana Chiefs Conference (representing 42 Alaska Native villages from 37 tribes) opposes drilling, as do at least 90 Native American tribes. The National Congress of American Indians (representing 250 tribes), the Native American Rights Fund as well as some Canadian tribes also oppose drilling in the 1002 area.

In May 2006, a resolution was passed in the village of Kaktovik calling Shell Oil Company "a hostile and dangerous force" that authorized the mayor to take legal and other actions necessary to "defend the community".[81] The resolution also calls on all North Slope communities to oppose Shell owned offshore leases unrelated to the ANWR controversy until the company becomes more respectful of the people.[82] Mayor Sonsalla says Shell has failed to work with the villagers on how the company would protect bowhead whales, which are part of Native culture, subsistence life, and diet.[82]

Moderate Republican House of Representatives member Carlos Curbelo and eleven others sent a letter to the Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, urging him to not include drilling in the December 2017 major tax rewrite, but the language remained in Senate-passed bill. Rep. Curbelo still voted for the final bill that included drilling.[83]

See also

[edit]- National Petroleum Reserve–Alaska

- Arctic policy of the United States

- Oil on Ice and Being Caribou, two documentary films about the Arctic Refuge drilling controversy.

- Petroleum exploration in the Arctic

References

[edit]- ^ Shogren, Elizabeth. "For 30 Years, a Political Battle Over Oil and ANWR". All Things Considered. NPR.

- ^ Solomon, Christopher (16 November 2017). "The ANWR Drilling Rights Tucked into the Tax-Reform Bill". Outside Online.

- ^ Burger, Joel. "Adequate science: Alaska's Arctic refuge". Conservation Biology 15 (2): 539.

- ^ United States. 96th Congress. "Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act". Fws.gov <"ANILCA Table of Contents". Archived from the original on 2008-08-28. Retrieved 2008-08-28.>. Retrieved on 2008-8-10.

- ^ "Potential Oil Production from the Coastal Plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: Updated Assessment". U.S. DOE. Archived from the original on 3 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- ^ Lee, Douglas B. (December 1988). "Oil in the Wilderness: An Arctic Dilemma". National Geographic. 174 (6): 858–871. S2CID 165885160.

- ^ Mitchell, John G. (1 August 2001). "Oil Field or Sanctuary?". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 5 January 2008.

- ^ Bohrer, Becky (14 May 2021). "Biden plans temporary halt of oil activity in Arctic refuge". AP News.

- ^ Frazin, Rachel (20 January 2021). "Biden nixes Keystone XL permit, halts Arctic refuge leasing". The Hill. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ a b D'Angelo, Chris (1 June 2021). "Biden Administration To Suspend Trump-Era Oil Leases In Arctic Refuge". HuffPost.

- ^ a b c "Biden to cancel oil and gas leases in Alaska issued by Trump administration". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ a b Jones, R. S. (June 1, 1981). "Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 (Public Law 92-203): History and Analysis Together with Subsequent Amendments" (Report No. 81–127 GOV). Government Division.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "ALASKANS DISPUTE 'FREEZE' ON LAND; Udall in Controversy Over State's Choice of Acreage". The New York Times. 11 June 1967.

- ^ Kovach, Bill (19 June 1978). "Bill on Future of Federal Lands in Alaska Generates Bitter and Emotional Controversy". The New York Times.

- ^ Rensberger, Boyce (31 October 1976). "Protection of Alaska's Wilderness New Priority of Conservationists". The New York Times.

- ^ "ALASKAN LANDS BILL SAVING VAST AREAS APPROVED BY HOUSE". The New York Times. 17 May 1979.

- ^ Schlosser, Kolson L. (January 2006). "U.S. National Security Discourse and the Political Construction of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge". Society & Natural Resources. 19 (1): 3–18. Bibcode:2006SNatR..19....3S. doi:10.1080/08941920500323096. S2CID 144418780.

- ^ King, Seth S. (3 December 1980). "Carter Signs a Bill to Protect 104 Million Acres in Alaska; Warning About Pollution A Balance Is Sought Allowing Oil Exploration Stevens Pledges Further Action". The New York Times.

- ^ Verrengia, Joseph B. (29 April 2001). "Test Well in Arctic Wildlife Refuge Keeps Its Secrets". Los Angeles Times. The Associated Press.

- ^ Eder, Steve; Fountain, Henry (2 April 2019). "A Key to the Arctic's Oil Riches Lies Hidden in Ohio". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Shabecoff, Philip (25 November 1986). "U.S. PROPOSING DRILLING FOR OIL IN ARCTIC REFUGE". The New York Times.

- ^ Fancy, S. G.; Whitten, K. R. (1 July 1991). "Selection of calving sites by Porcupine herd caribou". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 69 (7): 1736–1743. doi:10.1139/z91-242.

- ^ a b United Nations. Agreement Between the Government of the United States and the government of Canada on the Conservation of the Porcupine Caribou Herd New York: UNU. 1987.[1]

- ^ "Cox, R. Environmental Communication and the Public Sphere, 2013, Sage Publications"

- ^ Dionne, E. J. (3 April 1989). "Political Memo; Big Oil Spill Leaves Its Mark On Politics of Environment". The New York Times.

- ^ "Reaction to Alaska Spill Derails Bill to Allow Oil Drilling in Refuge". The New York Times. 12 April 1989.

- ^ a b c Murphy, Kim (7 August 1998). "Clinton to OK More Oil Drilling in Alaska Wilds". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b c d Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, 1002 Area, Petroleum Assessment, 1998, Including Economic Analysis (PDF) (Report). United States Geological Survey. April 2001.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey. (2002). Biological Science Report: USGS/BRD. Washington D.C.: USGS

- ^ "BUSH'S ENERGY BILL IS PASSED IN HOUSE IN A G.O.P. TRIUMPH". The New York Times. August 2, 2001. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ "House OKs Energy Bill, Drilling in Arctic Refuge". Los Angeles Times. August 2, 2001. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ "Bush wins vote on drilling in Alaska". The Guardian. August 3, 2001. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ "Senate Blocks Fuel Drilling in Alaska Wildlife Refuge". The New York Times. April 19, 2002. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ "Senate Blocks Oil Drilling in Arctic Reserve". Los Angeles Times. April 19, 2002. Retrieved July 2, 2024.

- ^ a b Waller, Douglas (13 August 2001). "Some Shaky Figures on ANWR Drilling". Time.

- ^ United States. House of Representatives. Bill Number H.R.6 for the 109th Congress. Archived 2008-11-12 at the Wayback Machine Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. 2005.

- ^ United States. The Congressional Budget for the United States Government for Fiscal Year 2006. Washington, D.C.: GPO. 2006.

- ^ Taylor, Andrew (10 November 2005). "House Drops Arctic Drilling From Bill". The Washington Post. The Associated Press.

- ^ Coile, Zachary (22 December 2005). "Senate blocks oil drilling push for Arctic refuge / GOP leaders hoping to override filibuster on defense spending bill fall 4 votes short". SFGATE.

- ^ Stolberg, Sheryl Gay (19 June 2008). "Bush Calls for End to Ban on Offshore Oil Drilling". The New York Times.

- ^ Sanders, Sam. "Obama Proposes New Protections For Arctic National Wildlife Refuge". Morning Edition. NPR.

- ^ Sabrina Shankman, 12 House Republicans Urge Congress to Cut ANWR Oil Drilling from Tax Bill, InsideClimate News (December 2, 2017).

- ^ www.whitehouse.gov . Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ D'Angelo, Chris (February 2018). "Trump Says He 'Really Didn't Care' About Drilling Arctic Refuge. Then A Friend Called". HuffPost. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- ^ Trump begins to speak at minute 1:40. "ANWR wildlife refuge". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Trump administration opens huge reserve in Alaska to drilling". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ Holden, Emily (12 September 2019). "Trump opens protected Alaskan Arctic refuge to oil drillers". The Guardian. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Plumer, Brad; Fountain, Henry (17 August 2020). "Trump Administration Finalizes Plan to Open Arctic Refuge to Drilling". The New York Times.

- ^ "U.S. approves oil, gas leasing plan for Alaska wildlife refuge". CBC News. The Associated Press. 17 August 2020.

- ^ Camden, Jim (September 9, 2020). "Washington leads suit against Arctic Refuge drilling". The Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ "Notice of Sale to be Issued for Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program Dec. 7". Bureau of Land Management (Press release). 7 December 2020.

- ^ "Trump Administration Rushes To Sell Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Land For Drilling". Science Friday. 11 December 2020.

- ^ Groom, Nichola; Rosen, Yereth (6 January 2021). "Oil drillers shrug off Trump's U.S. Arctic wildlife refuge auction". Reuters.

- ^ Energy Information Administration, 2008

- ^ a b c d e f g h United States. Department of Energy. Energy Information Administration. Analysis of Crude Oil Production in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. SR/OIAF/2008-03. Washington, D.C.: GPO. 2008.

- ^ United States. Department of Energy. Energy Information Administration. U.S. Crude Oil, Natural Gas, and Natural Gas Liquids Reserves Report Washington, D.C.: GPO. 2007.

- ^ United States. Department of Energy. Energy Information Administration. "Table of World Proved Oil and Natural Gas Reserves". Doe.gov. Retrieved on 2008-8-10.

- ^ USGS Release: USGS Oil and Gas Resource Estimates Updated for the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska (NPRA) (10/26/2010 12:43:17 PM). Usgs.gov. Retrieved on 2011-10-11.

- ^ United States. Department of Energy. Energy Information Administration. "Oil: Crude and Petroleum Products". Retrieved on 2019-08-27.

- ^ D'Angelo, Chris (1 February 2018). "Trump: 'I Really Didn't Care' About Drilling Arctic Refuge Until A Friend Called". HuffPost.

- ^ "President Applauds House Vote Approving Energy Exploration in Arctic National Wildlife Refuge" (Press release). Office of the Press Secretary. 25 May 2006.

- ^ "Energy for America's Future" (Press release). Office of the Press Secretary.

- ^ Today, Arctic (2023-09-07). "VOICE: Announcement Shows Biden Administration Prioritizes Their Agenda Over Local Indigenous Communities". ArcticToday. Retrieved 2024-02-05.

- ^ a b c CNN. "CNN/Opinion Research Corporation Poll". Pollingreport.com 29 July 2006. Retrieved on 2008-8-01.

- ^ Edge, Megan (28 September 2016). "2013's Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend check: $900". Anchorage Daily News.

- ^ Hill, Barry T. (31 October 2001). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: Information on Oil and Gas Activities in the National Wildlife Refuge System (Report). United States General Accounting Office. OCLC 54824669. DTIC ADA396490.

- ^ Davenport, Coral; Fountain, Henry; Friedman, Lisa (1 June 2021). "Biden Suspends Drilling Leases in Arctic National Wildlife Refuge". The New York Times.

- ^ Kluger, Jeffrey (2 November 2007). "The Eco Vote" (PDF). Time. p. 124.

- ^ Geraghty, Jim. "The Campaign Spot: John McCain interview". Archived 2008-06-21 at the Wayback Machine National Review 16 Jan. 2008.

- ^ United States. Department of Energy. Energy Information Administration. Petroleum and other liquids. Washington, D.C.: GPO. 2008.

- ^ Pierce, Melinda. "Drilling in the ANWR". Archived 2008-07-19 at the Wayback Machine Science Friday NPR. 2 Mar. 2001.

- ^ NRDC. "Drilling in the Arctic Refuge: The 2,000-Acre Footprint Myth".

- ^ United States Fish and Wildlife Service. "Wild Lands: Ecological Regions with a focus on the Coastal Plain and Foothills". Archived 2005-12-15 at the Wayback Machine 14 Feb. 2006. Retrieved on 2008-8-01.

- ^ World Wildlife Fund Canada. "Majority of Canadians Oppose Drilling in Arctic National Wildlife Refuge".[permanent dead link] 25 July 2005. Retrieved on 2008-8-01.

- ^ Alaska Inter-Tribal Council. "NCAI Resolution #BIS-02-056". Archived 2010-06-05 at the Wayback Machine 26 May 2005. Retrieved on 2008-8-01.

- ^ Wilderness Society. "Faces of Conservation". Retrieved on 2008-8-01.

- ^ "Gwich'in leader blasts Senate vote on ANWR drilling". Archived 2013-03-22 at the Wayback Machine Indianz.com 18 Mar. 2005. Retrieved on 2008-8-01.

- ^ Sands, Elizabeth, and Stephanie Pahler. "Native Communities" Columbia University. Retrieved on 2008-8-01. Archived September 1, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gwich'in Steering Committee. "Gwichʼin Niintsyaa Resolution". 10 June 1988. Retrieved on 2008-8-01.

- ^ Episcopal Public Policy Network. "FACTS: Native Opposition to Drilling". Archived 2005-12-24 at the Wayback Machine Episcopalchurch.org 15 Sep. 2005. Retrieved on 2008-8-01.

- ^ "Kaktovik resolution blasts Shell Oil". Archived 2009-03-01 at the Wayback Machine Juneau Daily News 24 May 2006.

- ^ a b Ragsdale, Rose (21 May 2006). "Kaktovik accuses Shell of insincerity". Petroleum News. 11 (21).

- ^ Daughtery, Alex. (6 December 2017). "House moderates oppose allowing Arctic oil drilling in tax bill". McClatchy DC website Retrieved 11 December 2017.

External links

[edit]- Official ANWR website, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- Oil on Ice, an anti-drilling documentary

- ANWR: Jobs, Energy, and Deficit Reduction, Parts 1 and 2: Oversight Hearings before the Committee on Natural Resources, U.S. House of Representatives, One Hundred Twelfth Congress, First Session, Wednesday, September 21, 2011 (Part 1); Friday, November 18, 2011 (Part 2)

- 1977 controversies in the United States

- 1977 in Alaska

- 20th century in Alaska

- 21st century in Alaska

- 20th century in the Arctic

- 21st century in the Arctic

- Petroleum in the United States

- Environmental controversies

- Environment of Alaska

- Legal history of Alaska

- National Wildlife Refuges in Alaska

- Native American history of Alaska

- North Slope Borough, Alaska

- Petroleum in Alaska

- Political controversies in the United States

- Political history of Alaska

- Industry in the Arctic

- Environmental issues in the United States

- Environmental impact of the petroleum industry

- Canada–United States relations

- Environmental racism in the United States